Thursday, July 9, 2015

First Steps in Quantum Computing-an update

Here is a Pdf file of a Pizza Seminar talk I gave in April 2013

Regularizing Divergent Sums-an update

Here is a Pdf file of a Pizza Seminar Talk I gave in September 2011.

Wednesday, April 3, 2013

A Stroll on Strange Spaces

Pizza Seminar Talk: Tuesday, April 9, 2013, 4:30-5:30 PM, MC 108.

Speaker: Mitsuru Wilson

Like the above ad promoting a potent Nitro NCG mixture, Noncommutative Geometry (NCG), as created by Alain Connes is a potent

mixture of many ideas in mathematics and physics.

One of the grand themes in mathematics, geometry, dates back for thousands of years. Starting from Euclidean spaces, many elementary shapes such as circles, disks, spheres have been studied until today; all spaces we learn in school are still studied today! Riemann then generalized Euclidean spaces with his foundation of manifolds, which was then used by Einstein for his theory which successfully encodes our knowledge of space-time and gravity.

With all they knew they did not understand quantum mechanics. The geometry is very fuzzy, uncertain, probabilistic and entangled there. Although it was introduced theoretically, this analogy works to explain noncommutative geometry (NCG) very accurately. The celebrated 1943 paper by Gelfand and Naimark proves the anti-equivalence (functors are contravariant) between (the

category of) compact Hausdor spaces X and (the category of) commutative C* algebras A. In the construction, A is nothing but C(X), the algebra of continuous functions . This correspondence gives rise to the viewpoint that any C* algebra is the space of functions C(X) of some noncomutative space X . They are fuzzy spaces in the sense that we cannot directly see them! My goal in this talk is to present the basic idea of Noncommutative Geometry in as elementary terms as possible and discuss a few canonical and fascinating examples in NCG.

Absolutely no background is necessary!

Speaker: Mitsuru Wilson

Like the above ad promoting a potent Nitro NCG mixture, Noncommutative Geometry (NCG), as created by Alain Connes is a potent

mixture of many ideas in mathematics and physics.

One of the grand themes in mathematics, geometry, dates back for thousands of years. Starting from Euclidean spaces, many elementary shapes such as circles, disks, spheres have been studied until today; all spaces we learn in school are still studied today! Riemann then generalized Euclidean spaces with his foundation of manifolds, which was then used by Einstein for his theory which successfully encodes our knowledge of space-time and gravity.

With all they knew they did not understand quantum mechanics. The geometry is very fuzzy, uncertain, probabilistic and entangled there. Although it was introduced theoretically, this analogy works to explain noncommutative geometry (NCG) very accurately. The celebrated 1943 paper by Gelfand and Naimark proves the anti-equivalence (functors are contravariant) between (the

category of) compact Hausdor spaces X and (the category of) commutative C* algebras A. In the construction, A is nothing but C(X), the algebra of continuous functions . This correspondence gives rise to the viewpoint that any C* algebra is the space of functions C(X) of some noncomutative space X . They are fuzzy spaces in the sense that we cannot directly see them! My goal in this talk is to present the basic idea of Noncommutative Geometry in as elementary terms as possible and discuss a few canonical and fascinating examples in NCG.

Absolutely no background is necessary!

First Steps in Quantum Computing

Discovery Cafe Talk: Tuesday, April 9, 5:30-6:30 PM, MC 108. Pizza to follow immeditaley after!

Speaker: Masoud Khalkhali

Public-key encryption and security of internet communications is based on a certain mathematical hypothesis:factoring a given integer N is a computationally difficult problem. The best current methods take about

$$ O(e^{1.9 (\log N)^{1/3} (\log \log N)^{2/3}})$$

operations. This is almost exponential in log N, the number of digits of N

A quantum computer, running Shor's algorithm, can factor N in

$$O((\log N)^3)$$

steps! This is polynomial in log N, or polynomial time, and a huge improvement over current methods.

This talk will introduce mathematics and physics ideas behind quantum computing and Shor's fast factoring quantum computing algorithm.

Friday, January 18, 2013

Random Walks and Brownian Motion

This Tuesday, Jan 15, we had our first Discovery Cafe meeting in 2013. I had promised before to give some introductory lectures on random walks and Brownian motions. So we started the year with this. Notice that now we meet at 3:30 PM on Tuesdays. Ruth took some notes and I am just using these notes here. I leave out many details. For references you can check out these two books: 1 and 2

There are two problems that at first look quite unrelated but our first task is to understand the close relation between the two. Random walks and the Dirichlet problem. In one dimension, on a finite set of points 0, 1, .....up to n, a walker randomly walks around. The chances of going forward or backward is % 50 each . Let P(i) be the probability of the random walker hitting the right end point n before hitting the end point 0, when he starts at i. Say point n is the jail, where the police can keep the drunk overnight, and point 0 can be the drunk's home. So we are looking at the probability that he will end up at the police station, versus ending up at home. This process is potentially infinite - the drunk can take up to an infinite number of steps back and forth without hitting either boundary. But never mind this at the moment and we neglect this possibility. We come back to this in the next week when we carefully define our probability space.

Finding the probability distribution P(i) is closely related to another problem, the discrete Dirichlet problem. We are looking for a function f(i) for i=1, ....n-1, with given boundary values f(0)=0 and f(n)=1, and such that f satisfies the equation

We say f has the mean value property. We shall see that this equation is the discrete analogue of

$$ \Delta f=0$$

where \( \Delta f = f'' \) is the second derivative operator, the Laplace operator in dimension one. Thus f can be regarded as a discrete harmonic function with given boundary values f(0) and f(n).

$$ \Delta f=0$$

where \( \Delta f = f'' \) is the second derivative operator, the Laplace operator in dimension one. Thus f can be regarded as a discrete harmonic function with given boundary values f(0) and f(n).

We checked that this Dirichlet problem has a unique solution. While a proof of this fact in dimension one is very easy and one can write in fact simple formula for f (what is it ?), existence of solutions in higher dimensions even in this discrete case is not totally trivial and in particular no simple formula exist. So the point of this probabilistic approach is that it works in all dimensions with minor modifications. First of all uniqueness follows from the following maximum principle:

Lemma (maximum principle): Any harmonic function achieves its maximum on the boundary points.

This easily follows from the mean value property. Then we used this maximum principle to prove uniqueness:

for any two solutions the difference \( f_1-f_2 \) is also a solution with boundary values equal to zero. This will violate the maximum principle unless \( f_1 = f_2 \) at all points.

Our next goal was to show that the the probability function P(i) has the mean value property. Since it clearly satisfies the required boundary conditions, this will prove that P is the harmonic function we were looking for. This is the first relation between random walks and the Dirichlet problem.

This all follows from a cute property of probabilities: Let X be a probability space, L and R be two mutually exclusive events that cover the whole X. Then for any event E we have

$$Prob (E)= Prob (E; L) Prob (L) $$

$$+ Prob (E; R)Prob (R)$$

Starting your random walk at i, let L = going left, R = going right, E = the event of getting to the end point n before getting to 0. Now it is not difficult to check, using the above probability identity, that P has the mean value property and since it clearly satisfies the boundary conditions it must be the solution of the Dirichlet problem.

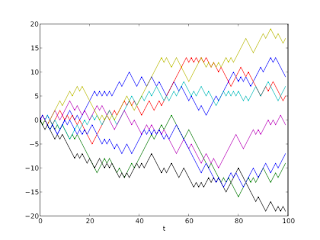

Next week we shall carefully defines the probability space X, as the space of all random walks and show how to define a probability measure on it, and will give a general formula for the solution in terms of integration over this path space. We shall then move to higher dimensions where things can get more even interesting! Here is graphs of some random walks all starting at the origin and going up to 100 steps.

This all follows from a cute property of probabilities: Let X be a probability space, L and R be two mutually exclusive events that cover the whole X. Then for any event E we have

$$Prob (E)= Prob (E; L) Prob (L) $$

$$+ Prob (E; R)Prob (R)$$

Starting your random walk at i, let L = going left, R = going right, E = the event of getting to the end point n before getting to 0. Now it is not difficult to check, using the above probability identity, that P has the mean value property and since it clearly satisfies the boundary conditions it must be the solution of the Dirichlet problem.

Next week we shall carefully defines the probability space X, as the space of all random walks and show how to define a probability measure on it, and will give a general formula for the solution in terms of integration over this path space. We shall then move to higher dimensions where things can get more even interesting! Here is graphs of some random walks all starting at the origin and going up to 100 steps.

Tuesday, November 27, 2012

Discovery Cafe Day 3: guest post by Jonathan Herman

In the cafe today,

more insight was given as to how mathematics is an ongoing process. In order to

discover and learn, a mathematician needs to be constantly asking why, and how?

Indeed, we had previously proved that there are infinitely many primes. But the

question today was, now what? What other questions can we ask to further

understand prime numbers? Who cares that there are infinitely many primes? How

is this theorem useful in discovering new concepts and ideas?

Some questions asked by the group included: Is there a pattern among the distribution of prime numbers? Are there infinitely many primes of the form \(n^2 + 1\)? How many prime numbers are there less than n, for any integer n? This last question was actually conjectured by Gauss and Legendre, and a strong approximation is given in the famous Prime Number Theorem. We discussed this interesting result:

$$ \pi(x) \sim \frac{x}{\log x} $$

i.e. \(\lim \frac{\pi(x) }{\log x /x} = 1 \, \, x\to \infty \), where \( \pi (x) \) is the number of primes less than \( x \). The group spent the rest of the time proving Euler’s amazing Product Formula and one of its consequences. See the other post about Day 3.

This powerful formula gave a classic example as to why a mathematician, or anyone, should be constantly asking “now what?” Indeed the group then proved an amazing corollary to this formula: that \( \sum \frac{1}{p} = \infty \). This proposition seems very strange indeed.

Some questions asked by the group included: Is there a pattern among the distribution of prime numbers? Are there infinitely many primes of the form \(n^2 + 1\)? How many prime numbers are there less than n, for any integer n? This last question was actually conjectured by Gauss and Legendre, and a strong approximation is given in the famous Prime Number Theorem. We discussed this interesting result:

$$ \pi(x) \sim \frac{x}{\log x} $$

i.e. \(\lim \frac{\pi(x) }{\log x /x} = 1 \, \, x\to \infty \), where \( \pi (x) \) is the number of primes less than \( x \). The group spent the rest of the time proving Euler’s amazing Product Formula and one of its consequences. See the other post about Day 3.

This powerful formula gave a classic example as to why a mathematician, or anyone, should be constantly asking “now what?” Indeed the group then proved an amazing corollary to this formula: that \( \sum \frac{1}{p} = \infty \). This proposition seems very strange indeed.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)